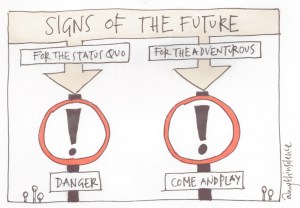

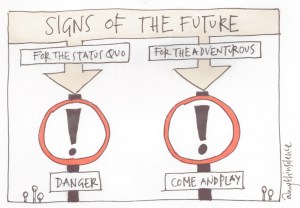

Staying where we are isn’t difficult, but it is dangerous.

Equilibrium, embedded in establishment and complacency, is a most dangerous place to be.

Moving to the edges isn’t as dangerous as we think, but it is difficult.

Disequilibrium, expressed in alertness, industry, and freshness, is our best hope.

Richard Pascale, Mark Millemann, and Linda Gioja argue we have a lot to learn from nature – which makes sense as we are species within it:

‘Coping mechanisms that have atrophied during long periods of equilibrium usually prove inadequate for the new challenge. Survival favours heightened adrenaline levels, wariness, and experimentation. Alfred North Whitehead got it right, “Without adventure, … civilisation is in full decay.” … At certain scales (i.e., small) and in some frames (i.e., short), equilibrium can be a desirable condition. But over long intervals of time and on the very large scales, equilibrium becomes hazardous. Why? Because the environment in which an organism (or organisation) lives is always changing. … Prolonged equilibrium dulls an organism’s senses and saps its ability to rouse itself appropriately in the face of danger.’*

There is always a new challenge: if I can’t see the challenges then I’m not really looking.

Part of what we might call equilibrium-thinking is trying to face a new challenge with an old solution. This thinking also gets lost in time, merging what look to be safe periods of equilibrium into the kind of hazard Pascale, Millemann, and Gioja are warning of.

In the West, we’re often getting on with life, getting things done, finding quick answers: ‘The result of a pragmatic, individualistic, competitive, task-orientated culture is that humility is low on the value scale.’** This humility equates to wariness as mentioned by Pascale, Millemann,and Gioja.

I see prophetic communities living alternative realities, playing the infinite game.^ It may be difficult for everyone to be as alert and adaptive as they are, but they make it possible for new ways to be discovered by others. Even when those within the established culture wake up to what is happening, they often do not possess the skills acquired on the edges. Here is Peter Senge describing a movement away from competition to collaboration:

‘Fortunately, more people are discovering that collaboration is the human face of systems thinking. Collaborating successfully requires more than good intentions. It also requires improving your “convening” skills so that you can get the right people together and have more open and productive meetings.’^^

Prophetic communities hone the new skills whilst supporting their members – the very skills others need. Above everything else, they value the way of humble inquiry. Though their questions are seen as uncomfortable and dangerous, and are difficult, they bring a freedom of adventurous thought and concern for all.

(*From Richard Pascale, Mark Millemann, and Linda Gioja’s Surfing the Edge of Chaos.)

(**From Edgar Schein’s Humble Inquiry.)

(^The infinite game is a reference to James Carse’s description of a game marked by including as many as possible for as long as possible, and when the rules get in the way of these two values, they are changed: Finite and Infinite Games.)

(^^From Peter Senge’s The Necessary Revolution. Systems thinking refers to seeing the whole picture of how operating systems often have other systems around them, which make them work, or not.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.