Today the funeral of my father-in-law Derek takes place, and his family and friends will be gathering to remember and give thanks for a life that was quietly full of so many things, and most of all, his family.

I’ve just discovered that the national flower of Ukraine is the sunflower.

We’re going to be connecting this to our 2022 sunflower festival for the housing estate we live on.

It will also link in to another initiative being planned that I’ll share with you as soon as I am able to.

The great thing about sunflowers is that they’ll grow virtually everywhere.

If today was a holiday in your honour, what would it be about?*

Seth Godin

Add to this Rob Walker’s idea** of pulling out a picture you’ve taken of a place and revisit to see how it’s changed.

Mix them up a little and now you have the idea of revisiting yourself, say, ten years ago, noticing what you’re doing now that you weren’t doing then that is important to you and is the things you’d be remembered for?

Of course, this isn’t about looking for a day to honour ourselves, it’s about doing more of what you’ve noticed in ever more imaginative ways for the sake of others.

*From Seth Godin’s blog: How would we celebrate your day?;

**From Rob Walker’s blog: Be a (Re)Visitor.

In a world geared for hurry, the capacity to resist the urge to hurry – to allow things to take the time they take – is a way to gain purchase on the world, to do the work that counts, and to derive satisfaction from the doing itself, instead of deferring all your fulfilment to the future.*

Oliver Burkeman

Instead of calling everything a game, we should think of everything as playable: capable of being manipulated in an interesting and appealing way within the confines of its constraints.**

Ian Bogost

When we slow down, we are able to reconnect playfulness with seriousness.

Oliver Burkeman counsels how we must ‘slow down to the speed that art demands’.*

John O’Dohonue anticipates this when he writes,

This is what all art strives for: the creation of a living permanence.^

Whatever the most artful and lasting things are that we produce through our living, they are not going to happen in a hurry.

I’ll be taking to heart the three “rules of thumb” provided by Burkeman for exploring the power of patience:

The first is to develop a taste for having problems. … The second principle is to embrace radical incrementalism. … The final principle is that, more often than not, originality lies on the far side of unoriginality.*

I connect the first with the first elemental truth of “Life is hard,” that life is working on one problem after another, but a life without problems would be a boring life.

The second is about turning up, doing a little often. I connect this with the response of faithfulness: finding small ways to do what I value and what I do, every day.^^

The third encourages me to trust the path with a heart, that may not be original at the outset but will bear fruit as my slow journey in the same direction.

*From Oliver Burkeman’s Four Thousand Weeks;

**From Ian Bogost’s Play Anything;

^From John O’Donohue’s Benedictus:

^^Something I will take to heart for beginning that second book.

once the attention economy has rendered you sufficiently distracted, or annoyed, or on edge, it becomes easy to assume that this is just what life inevitably feels like*

Oliver Burkeman

You can stop doing these [atelic] things, and and you eventually will, but you cannot complete them.**

Kieran Setiya

It was 8pm and I could finally rest, except that my football team was playing and I wanted to keep watching that alongside the the last episode of the box set that we had to watch and the hotel rooms that needing booking – all before we begin a journey towards sleep in ninety minutes time.

I cram my day with things that have a purpose or outcome, some telos or other, but I know I need to enter into the atelic and find rest.

*From Oliver Burkeman’s Four Thousand Weeks;

**Kieran Setiya, quoted in Oliver Burkeman’s Four Thousand Weeks.

One way of understanding capitalism, in fact, is as a giant machine for instrumentalising everything it encounters – the earth’s resources, your time and abilities (or ‘human resources) – in the service of future profit.*

Oliver Burkeman

Who is it he is trying to teach? To whom is he explaining his message? To children weaned from their milk, to those just taken from the breast? For it is: Do this, do that, a rule for this, a rule for that; a little here, a little there.**

Thank you, Oliver Burkeman. I get it.

To be present in this moment and enjoy it for what it is:

Our obsession with extracting the greatest future value out of our time blinds us to the reality that, in fact, the moment of truth is always now – that life is nothing but a succession of present moments, culminating in death, and that you’ll probably never get to a point where you feel yo have things in perfect working order.*

May I reset and start over?

I guess I don’t get the 62+ years back?

Thought not.

We learn ways that take us from the present to rueing the past and worrying about the future, and whilst there is value in reflecting on the past mistakes so as not to make them again and imagining a better future that removes pain for someone, we have developed these out-of-the-present tactics to an industrialised level.

One day, we’ll enjoy life more, we say but until then we must work work work and distract distract distract.

We are taught that everything has to have future value: To what end?

Even mindfulness can be practised with an end goal in mind: one day I will be less distracted, less agitated, more tranquil.

But maybe my enjoying the books I’m reading and the thoughts I’m encountering and the doodling I’m engaging in and the ideas I’m playing with as I write this post are just moments of nowness to be in?

And what you’re viewing is a happy accident from these moments of presence and enjoyment, that I need to keep bringing myself kindly back to for them to be what they can be.

*From Oliver Burkeman’s Four Thousand Weeks;

**Isaiah 28:9-10.

You can’t just be you. You have to double yourself. You have to read books on subjects you know nothing about. You have to travel to places you never thought of travelling. You have to meet every kind of person and endlessly stretch what you know.*

Mary Wells

Attention … just is life: your experience of being alive consists of nothing more than the sum of everything to which you pay attention. At the end of your life, looking back, whatever compelled your attention from moment to moment is simply what your life will have been.**

Oliver Burkeman

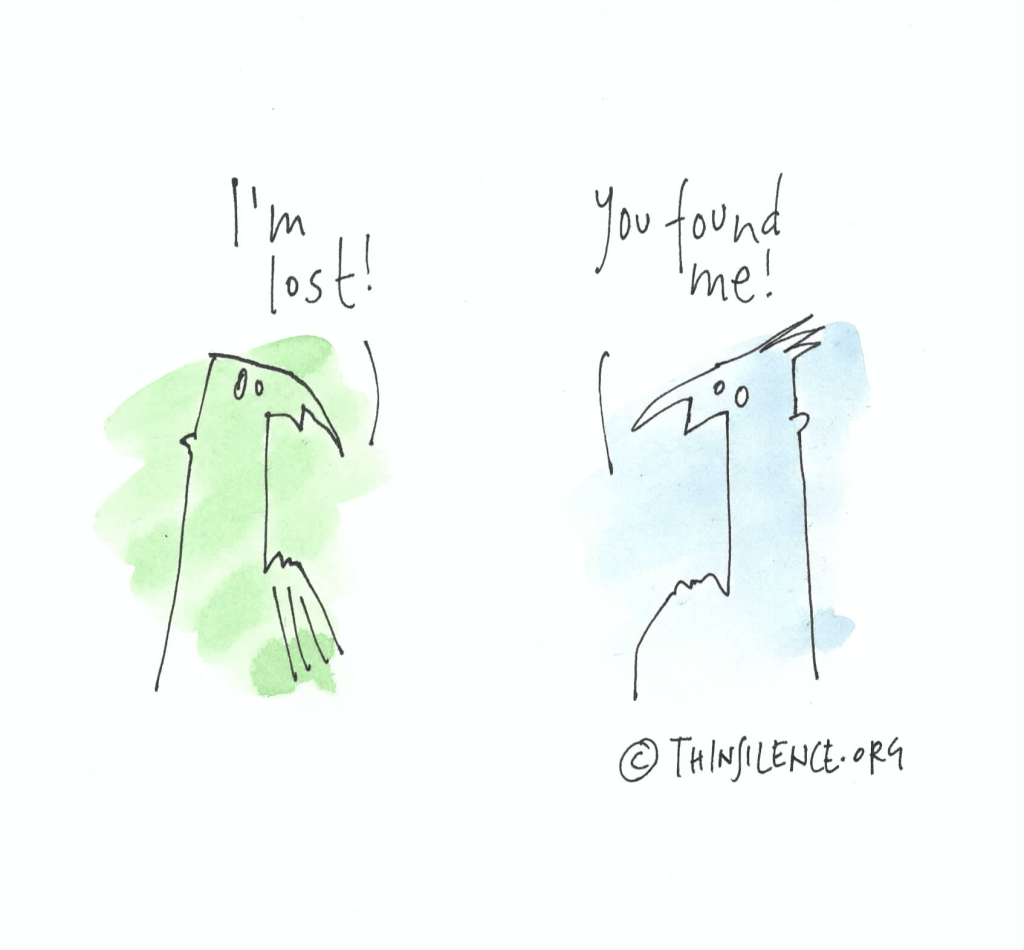

We like being found – when we have something to do, a journey has to be made, someone asks a question – but allowing ourselves to be lost is how life becomes, well, more alive.

And as soon as we feel found, it’s time to get lost again.

*Mary Wells, quoted in gapingvoid’s blog: Always open self;

**From OlIver Burkeman’s Four Thousand Weeks.

People go out to their work and to their labour until the evening.*

A job is made fun not by turning it into a game, but by deeply and deliberately pursuing it as a job. … We don’t play to distract ourselves from the world, but in order to partake in it.**

Ian Bogost

When the experience is painful, boring, or difficult, we’re tempted to distract ourselves, but, as Seth Godin helpfully identifies,

You can discover overlooked value by measuring things that are difficult to measure.^

All things are playable.

Turning towards the pain may provide personal insight, growth and transformation, turning towards the boring may result into previously unimagined possibilities, turning towards the difficult may lead us into collaborations and breakthroughs.

*Psalm 104:23;

**From Ian Bogost’s Play Anything;

^From Seth Godin’s blog: The easy measurements.

Oliver Burkeman warns against ‘the flawless standards of the imagination’.*

Our problem is that we can imagine multiple perfects.

At first these delight us but soon they tyrannise.

We don’t know where to begin to give expression to what is so wonderfully imagined.

And if we do start, we struggle to finish.

Good enough is a great place to begin, and it may even be more than enough to finish.

And good enough can always get better.

*From Oliver Burkeman’s Four Thousand Weeks.

You must be logged in to post a comment.