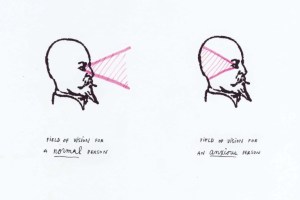

‘In conversation, the interval of time that elapses between the other person’s sentiment or question and my father’s response greatly exceeds the average, a lapse swelling with Kierkegaard’s assertion that “the moment is not properly an atom of time but an atom of eternity.”’*

Maria Popova is commenting on her father’s slow response to others’ thoughts and inquiries. She came to understand how this was not about the difficulty of the subject matter or conundrum, but about empathy:

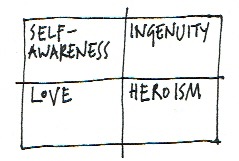

‘It turns out that my father’s liberal pauses are so discomposing because our experience of time has a central social component — an internal clock inheres in our capacity for intersubjectivity, intuitively governing our social interactions and the interpersonal mirroring that undergirds the human capacity for empathy.’*

It feels like the internet, and social media in particular, is the opposite of this slow empathy. Popova’s words had caught my attention as I’d been thinking about how life was to be found more in questions than in answers we often we can rush towards. We’ll only truly know the true worth of many people and many things in the future we cannot see, perhaps one we will not even live to see. It means we are best served by openness rather than closed-ness. If, then, we say we don’t care about what the whole truth or picture is then we’re reducing if not eliminating empathy.

Is it possible, then, to live our whole lives wondering?

I am reminded of Mary Oliver’s words which I posted a few days ago:

“When it’s over, I want to say: all my life

I was a bride married to amazement.

I was a bridegroom , taking the world into my arms.”**

I read a little more from Bernadette Jiwa after reflecting on Popova’s story. Jiwa is outlining practices to help us notice more: I find myself reading about the practice of identifying the backstory:

‘What new things did you learn about the person?

How does that change the way you feel about them?”^

Jiwa had been listening to her father speak about his working life, discovering that he had more than twenty five jobs in his lifetime:

‘You’re looking to gather insights here, not just about what people do, but also about why they do it.’^

This involves inquiry, and not assuming we know the answers. It is about empathy, about understanding what makes another tick. Elsewhere Jiwa has written:

‘Your purpose is not what you do but why you do it.’^^

If we are to see deeper into one another, we will need to live in questions rather than answers.

I hope I’m move trying to offer an answer, rather, uncovering of a question.

(*From Maria Popova’s BrainPickings: Empathy is a Clock that Ticks in the Empathy of Another.)

(**Mary Oliver, quoted bin Philip Newell’s The Rebirthing of God.)

(^From Bernadette Jiwa’s Hunch.)

(^^From Bernatte Jiwa’s Difference.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.