These past days and weeks have reminded all of us how dangerous this planet can be, how life is full of danger. This is where we live, where we have to explore, to see and understand “just because” but also to try and and make life better for one another as a result.

When it comes to exploring, Seth Godin catches my attention when he suggests “living in a shepherd’s hut” in order to see whether this “piece of land” is where we want to build something more permanent:

‘Get as close as you can to the real thing, live it, taste it, and then decide how to build your career or your organization.”*

There’s a sense of adjacent possibility in this – to see whether there’s something else we may want to make into a different and permanent experience of life. Because there’s something naturally resistant in us to trying on an idea or a space or a kind of work or some different kind of interest, the shepherd’s hut makes it possible to do something in a temporary way.

It may just make it possible for us to venture out into the expansive.

Frans Johansson points out that will be open to more “click moments” – his phrase for when our skills and the happenstance and serendipity of the universe are married together, if we “take our eyes of the ball”:

‘Conscientiousness is […] the type of behaviour that insures execution but also allows us to miss greater ideas, projects, improvements or connections that keep popping up around us. Unfortunately, by rigidly pouring all of our effort into one approach we miss out on the unexpected paths to success.’**

I find myself thinking about adjacent lives – offering other ways for living out our talents, passions, and experiences, and which we can explore in impermanent ways.

Conscientiousness, then, is our enemy, hiding from us the expanse that is within and the expanse that is out there:

“Listen to your life. See it for the fathomless mystery it is.”^

“When we walk, we naturally go to the fields and woods: what would become of us, if we walked only in the garden or a mall?”^^

I found these words from Henry David Thoreau being quoted by Rebecca Solnit in her unwrapping of the beginnings of walking for pleasure. The identification of this happens towards the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth centuries: siblings William and Dorothy Wordsworth refer to long walks through the Lake District just for the pleasure of walking, here captured in one of William’s most famous poems:

‘I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o’er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host, of golden daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.’*^

Walking, especially wandering or dawdling, offers itself as a perambulatory expression of the shepherd’s hut – becoming a way for us to join together the internal and external expanses. After reading Iris Murdoch and Seth Godin describing what is an artist, I wonder whether this word is simply a way for describing those of us who are discovering some way or other to connect the inward and outward expanses:

Iris Murdoch writes of art:

‘But the greatest art is ‘impersonal’ because it shows us the world, outworld and not another one, with a clarity which startles us and delights us simply because we are not used to looking at the real world at all.’^*

The adjacent possibility is that which is right under our noses but we have no way of seeing it – back to Johansson’s remark earlier. Seth Godin directs our attention to what artists (he is thinking of everyone being an artist) are trying to deal with – reminding us that we live in a dangerous world and our lives are full of danger:

‘An artist is someone who brings humanity to a problem, who changes someone else for the better, who does work that can’t be written down in a manual.’⁺

The inward and the outward are entwined in an expansive way.

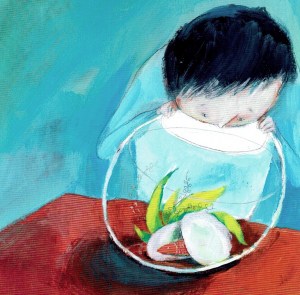

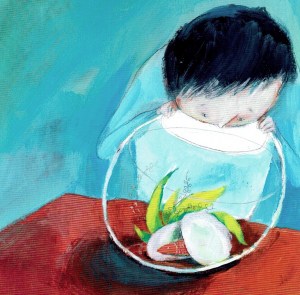

In their beautiful book This is a Poem that Heals Fish, Jean-Pierre Siméon and Olivier Tallec tell and illustrate the story of Arthur whose fish Leon has a problem:

‘- Mommy, my fish is going to die!

Come quickly! Leon is going to die of boredom!

Arthur’s mommy looks at him.

She closes here eyes,

she opens her eyes …’⁺⁺

How do you heal a fish from boredom? How do you heal anyone from boredom? Here’s is Arthur’s mum’s way:

‘Then she smiles:

– Hurry, give him a poem!

And she leaves for her tuba lesson.”⁺⁺

But wait …

‘A poem!? But what

is a poem?’⁺⁺

This is Arthur’s quest.

We each have a quest.

(*From Seth Godin’s blog: Can you live in a shepherd’s hut?)

(**From Frans Johansson’s The Click Moment.)

(Frederick Blechner, quoted in the Northumbria Community‘s Morning Prayer.)

(^^Henry David Thoreau, quoted in Rebecca Solnit’s Wanderlust.)

(*^From William Wordsworth’s I wandered lonely as a cloud.)

(^*From Iris Murdoch’s The Sovereignty of Good.)

(⁺From Seth Godin’s Whatcha Gonna Do With that Duck?)

(⁺⁺From Jean-Pierre Siméon and Olivier Tallec’s This is a Poem that Heals Fish.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.