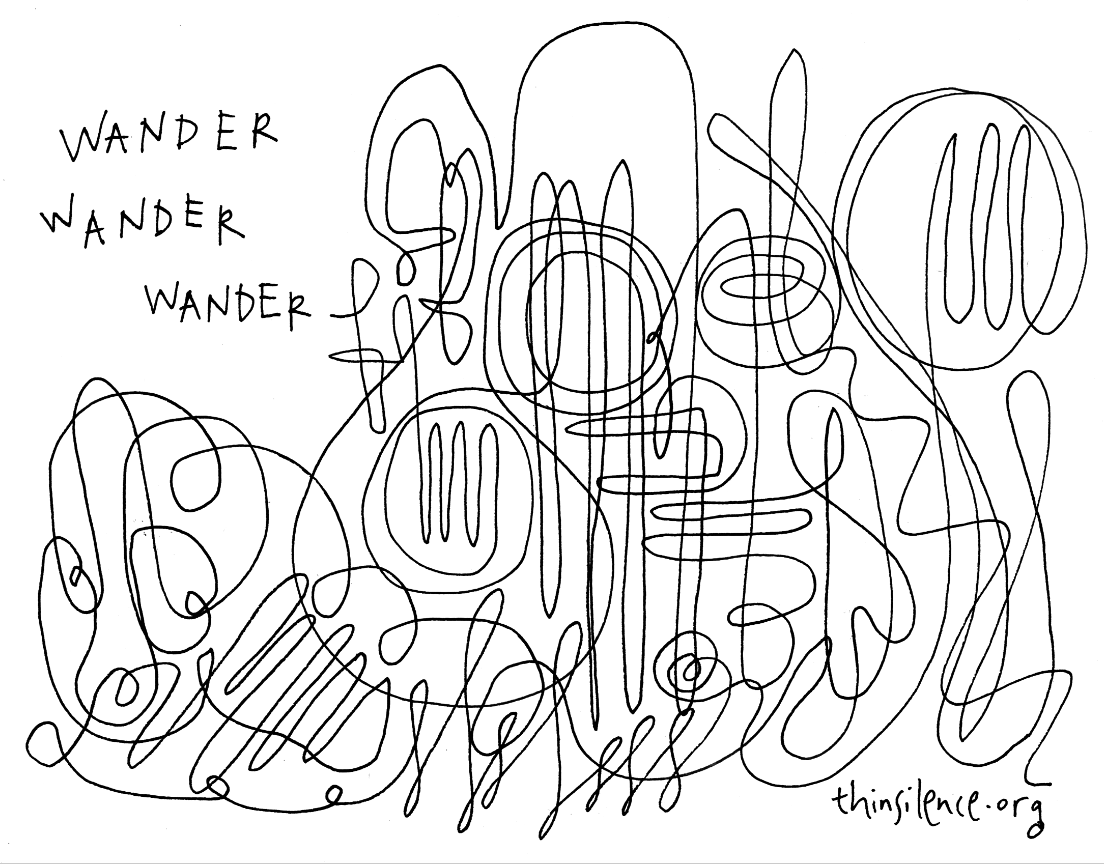

Part of what makes roads, trails and paths so unique as built structures is that they cannot be perceived as a whole all at once by a sedentary onlooker. They unfold in times just as a story does as one listens or reads, and a hairpin turn is like a plot twist, a steep ascent a building of suspense to the view at the summit, a fork in the road as an introduction of a new storyline, arrival the end of a story.*

(Rebecca Solnit)

There has to be training to help you open your ears so that you can begin to hear metaphorically instead of concretely.*

(Joseph Campbell)

As I sit down with my journal at the beginning of a day, I have no idea what I will be specifically reading about, what the appearing theme will be, how disparate thoughts and ideas may or may not come together as I happen upon them along the way.

In Ali Smith’s Autumn the old man that is Daniel Gluck has just been told by the young Elisabeth Demand of the last book she’d read:

‘And what did it make you think about? Daniel said.

Do you mean, what was it about? Elisabeth said.

If you like, Daniel said.^

A road, like a book can be described in at least two ways: what it was like and what happened to us on the way. Journaling, like a road, is not about what I read about but about the possibilities opening up to me:

“So far the evidence is compelling. What seems to be happening is that information is coming from the future.”^^

The person who got me started doodling, Hugh Macleod, writes of growing up in 1980s Edinburgh. Now he’s in Miami. Along the way he developed some great art and thinking.

Now I’m in Edinburgh.

I had wanted to stay in Northallerton but couldn’t.

I moved to Blackburn and wanted to stay there but couldn’t.

Then there was a move to Oldham and I wanted to stay there, but couldn’t.

Now I’m glad I wasn’t able to stay in any of these places.

Edinburgh hasn’t been a destination but a journey. The journey from Northallerton to Edinburgh, now around twenty five years long, has been one that has changed me on the inside.

The inside is what the road changes, and the inside is what changes the road.

(*From Rebecca Solnit’s Wanderlust.)

(**From Joseph Campbell and Bill Moyer’s The Power of Myth.)

(^From Ali Smith’s Autumn.)

(^^Brian Johnson, quoted in Joseph Jaworski’s Source.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.